The history of automated controls of inspired oxygen goes back many decades, to before the invention of pulse oximetry. The first studies I remember used transcutaneous PO2 as the target variable, which had major limitations, as well as the advantage of being better at detecting hyperoxia, at least when it was working well.

There are numerous recent publications about automated FiO2 control, at the end of this post I have put a list of a selection of publications from the last 8 years or so. Such systems have usually been shown to reduce the time an infant spends outside of the desired saturation range, and to reduce the need for nursing intervention.

The different systems use different algorithms, and thus their efficacy in improving “time in range” differs. One of the publications below (Salverda et al) compared outcomes of 2 epochs using different controllers. They had previously noted a major difference in efficacy of the systems in reducing hyperoxia, with the OxyGenie system on the SLE6000 ventilator being much better at reducing hyperoxia than the CliO2 system on the Avea ventilator; but with similar efficacy in terms of percentage time in hypoxia. The clinical outcomes of the babies were different between the 2 epochs, with the OxyGenie epoch having fewer babies developing severe RoP, shorter duration of invasive ventilation, and shorter hospitalisation.

One big concern I have is that increasing FiO2 when an infant is apnoeic is unlikely to improve their oxygenation! Intermittent hypoxic episodes are mostly due to apnoeic pauses, and increasing the FiO2 during such pauses will likely have no impact on the depth of the hypoxia, but may lead to post-apnoeic hyperoxia. It is, unfortunately, difficult to tell if an infant is actually breathing. Central apnoeas are easy to detect, but obstructive apnoeas, and the obstructive component of mixed apnoeas, cannot be easily detected.

The algorithms should be designed to avoid changes in FiO2 during respiratory pauses, but rather to adjust FiO2 when the infant is breathing and their requirements for oxygen change. Exactly how to do that I am not sure; to determine whether an infant is actually breathing, a unidirectional noise-cancelling microphone attached to the chest, with the appropriate software for detection of breath sounds, is an idea I had many years ago and wasn’t able to pursue. Anyone who wants to investigate that idea, feel free.

Randomized trials, without crossover to periods of manual control, have been very few. One small trial listed below was from King’s College in London (Kaltsogianni et al), with only 70 babies in total, using the OxyGenie system on the SLE6000. Babies of GA 22-34 weeks (mean about 27) were enrolled, and randomized to automated vs manual control. The automated group had less hypoxia and less hyperoxia, and had improved clinical outcomes, shorter mechanical ventilation and less BPD.

What was needed was a large multicentre RCT. (Franz AR, et al. Automatic versus manual control of oxygen and neonatal clinical outcomes in extremely preterm infants: a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2026;10(3):179–88) In this trial performed in China, Germany (80% of the subjects), the Netherlands and the UK, infants of 23 to <28 weeks GA were randomized, within 96 hours of birth, to either automated FiO2 control, using whatever ventilator system was available, or manual control, if possible using the same ventilator. A variety of systems were used, most commonly the Stephan Sophie ventilator, at just over half of the sites, followed by the Leoni+ at another 8 sites. The primary endpoint was a composite of any of the following: death, necrotising enterocolitis, or bronchopulmonary dysplasia up to 36 weeks PMA, or severe retinopathy of prematurity by 44 weeks PMA. I have no idea why death was only of interest up to 36 weeks, while the infants were followed in any case until 44 weeks. I don’t know if there were any deaths after 36 weeks.

The study was designed to have 2340 infants enrolled, but, because of recruitment difficulties, the analysis and the sample size had to be adjusted, and 1080 infants were finally included.

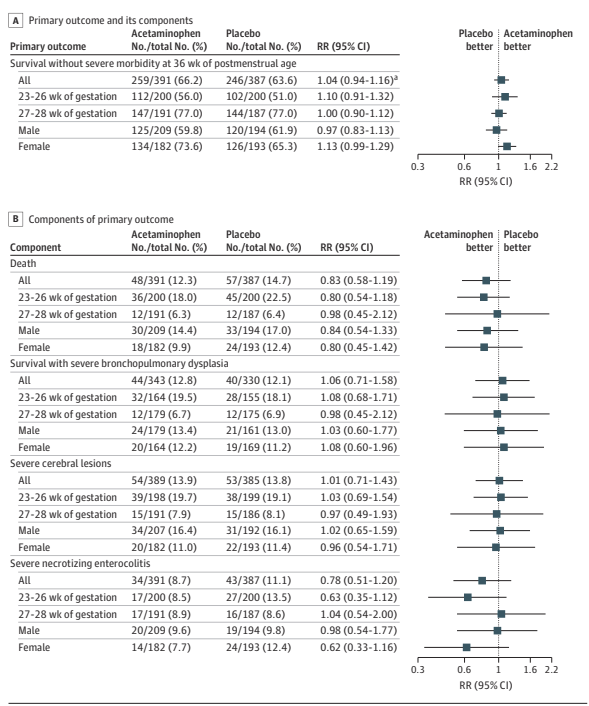

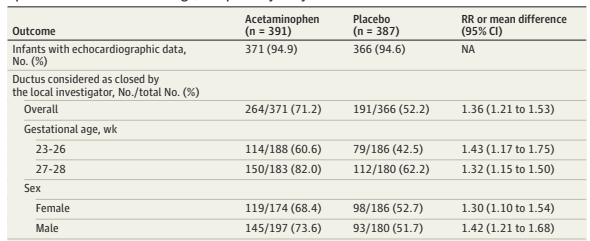

There were no major differences in any of the outcome measures, or in the primary, composite, outcome. The primary outcome was 2.7% less frequent among intervention group babies (Absolute difference). In a subgroup analysis, the FiO2 control with ventilator “3” (which they are careful not to name but was used in over half the infants, and therefore must have been the Stephan Sophie) was associated with a larger reduction in the primary outcome, from 41% to 35%, while the other 2 ventilators had slightly worse outcomes in the FiO2-control groups, by 2 or 4%. One always has to be very careful about such subgroup analyses, and the interaction term was not ‘significant’, but it does suggest the possibility that the impact of the automated control differed by algorithm. The BPD part of the primary outcome was significantly different by subgroup of ventilator/algorithm type, again showing a greater reduction with ventilator 3 (17% vs 23%) in the FiO2 control group.

This study did not measure the impacts on nursing workload, or alarm fatigue, 2 things that may be positively impacted by automated FiO2 control.

Currently none of these systems are available in north America, largely because of a lack of trials such as this. From my fairly limited review of this large literature, it seems that the most promising algorithms are the OxyGenie on the SLE6000, which was not used in this recent RCT, and the Stephan Sophie with SPO2C, which was. This trial, with its lack of a clinical benefit, at least showed no safety concerns.

It is hard to argue with a large multicentre trial such as this, but it is also hard to imagine that spending less time hypoxic, and less time hyperoxic, will not eventually be proved to have benefits for our patients.

A Selection of Recent Publications

Dani C, et al. Cerebral and splanchnic oxygenation during automated control of inspired oxygen (FiO2 ) in preterm infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021.

Dani C. Automated control of inspired oxygen (FiO2 ) in preterm infants: Literature review. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(3):358–63.

Poets CF, Franz AR. Automated FiO2 control: nice to have, or an essential addition to neonatal intensive care? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016.

Wilinska M, et al. Automated FiO2-SpO2 control system in neonates requiring respiratory support: a comparison of a standard to a narrow SpO2 control range. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):130. Kaltsogianni O, et al. Closed-loop automated oxygen control in preterm ventilated infants: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025.

Brouwer F, et al. Comparison of two different oxygen saturation target ranges for automated oxygen control in preterm infants: a randomised cross-over trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2024;109(5):527–34.

Langanky LO, et al. Pulse oximetry signal loss during hypoxic episodes in preterm infants receiving automated oxygen control. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;183(7):2865–9.

Salverda HH, et al. Clinical outcomes of preterm infants while using automated controllers during standard care: comparison of cohorts with different automated titration strategies. 2022:fetalneonatal–2021–323690.

Salverda HH, et al. The effect of automated oxygen control on clinical outcomes in preterm infants: a pre- and post-implementation cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(7):2107–13.

Ali SK, et al. Preliminary study of automated oxygen titration at birth for preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022:fetalneonatal–2021–323486.

Dargaville PA, et al. Automated control of oxygen titration in preterm infants on non-invasive respiratory support. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022;107(1):39–44.

Sturrock S, et al. A randomised crossover trial of closed loop automated oxygen control in preterm, ventilated infants. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(3):833–7.

Sturrock S, et al. Closed loop automated oxygen control in neonates – a review. Acta Paediatr. 2019.

Gajdos M, et al. Effects of a new device for automated closed loop control of inspired oxygen concentration on fluctuations of arterial and different regional organ tissue oxygen saturations in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018.